Lolis Edward Elie, longtime New Orleans civil rights attorney, dies at 87 (or 89)

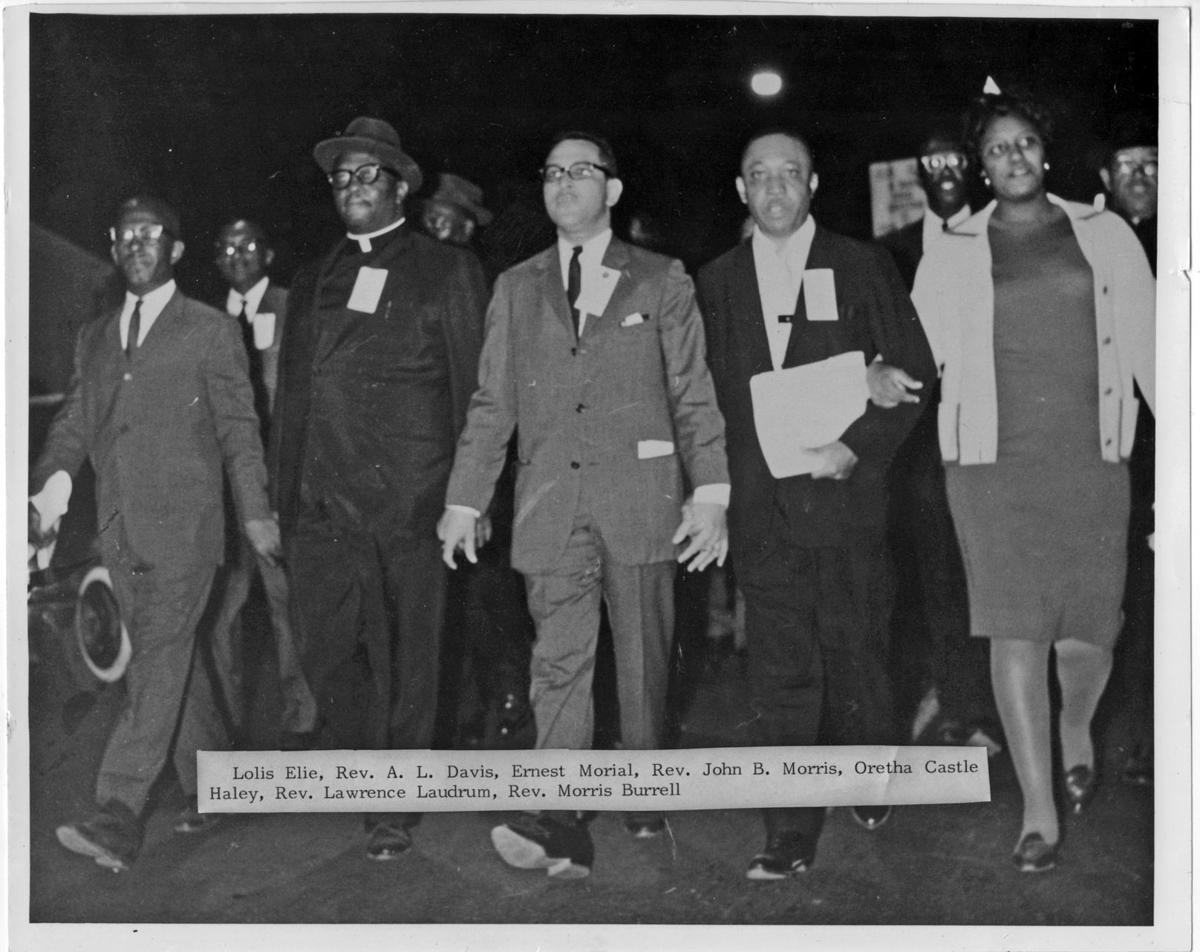

Photo by Ray Ariatti, courtesy of Loyola University -- Lolis Edward Elie, Rev. A.L. Davis, Ernest "Dutch" Morial, Rev. John B. Morris and Oretha Castle Haley, right, parade during the September 30, 1963 Freedom March in New Orleans.

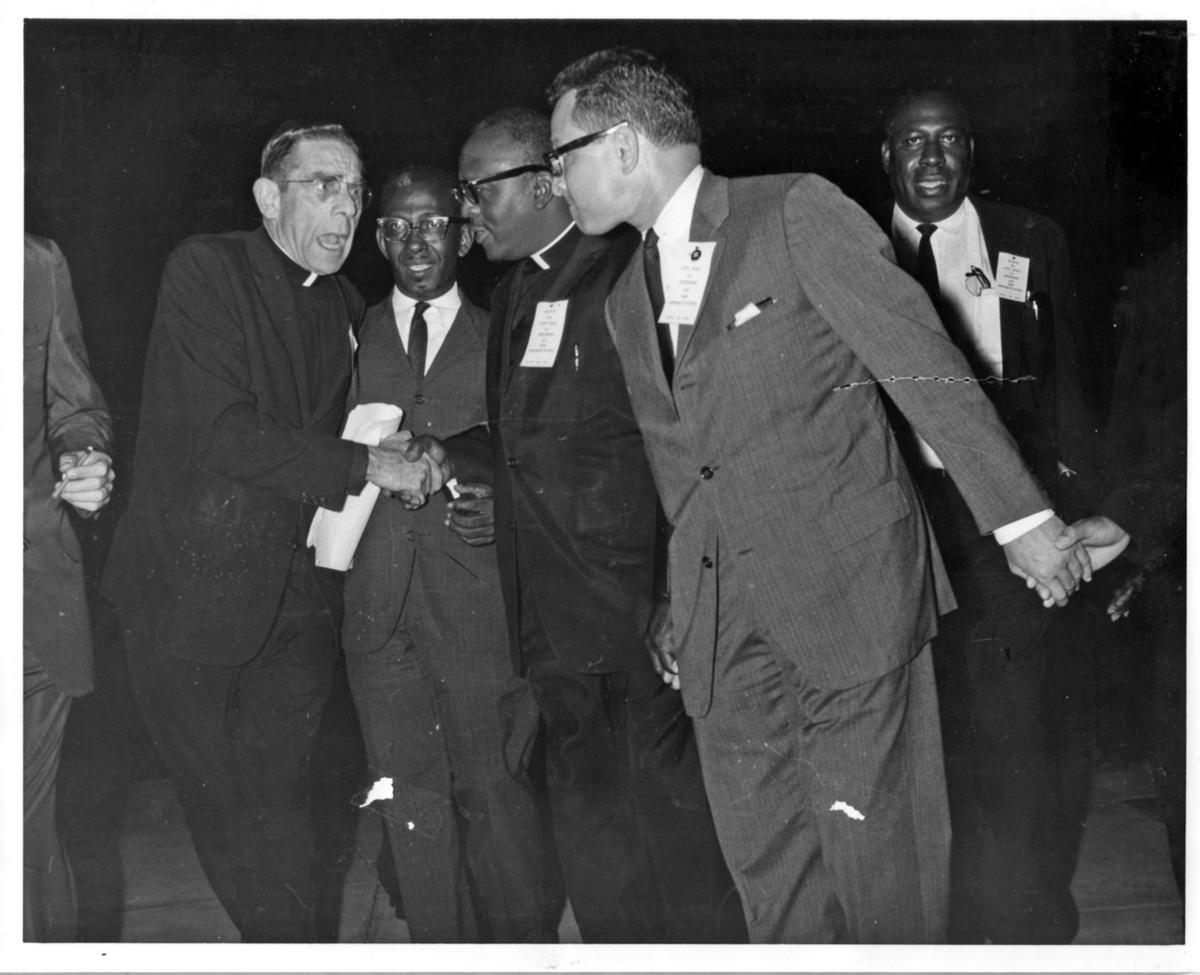

Photo by Ray Ariatti, courtesy of Loyola University -- Jesuit priest Louis J. Twomey greets Lolis Edward Elie, second left, the Rev. A.L. Davis, Ernest "Dutch" Morial, and Rev. Avery Alexander during the September 30, 1963 Freedom March in New Orleans.

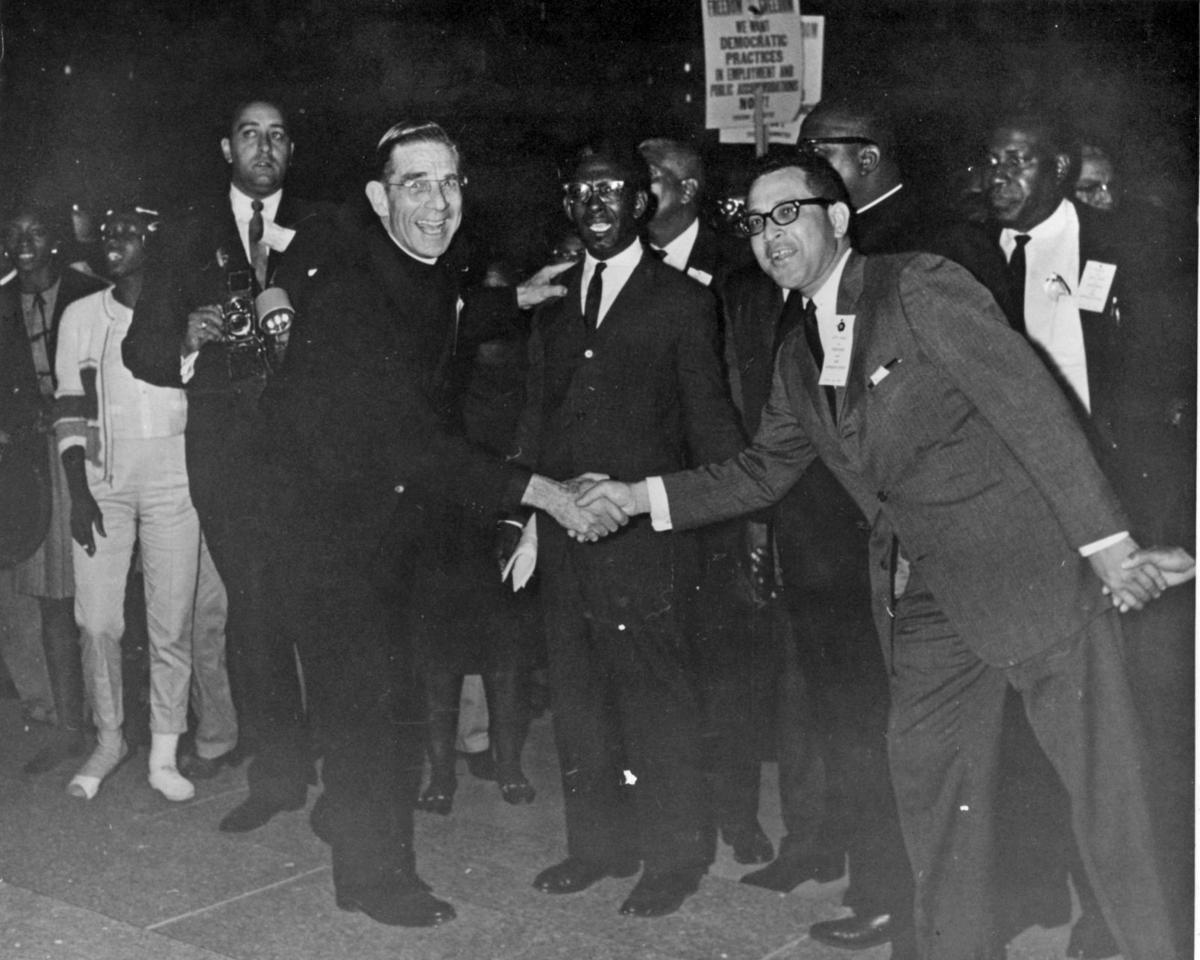

Photo by Ray Ariatti, courtesy of Loyola University -- Jesuit priest Louis J. Twomey greets Lolis Edward Elie, center, and shakes hands with Ernest "Dutch" Morial, right, during the September 30, 1963 Freedom March in New Orleans.

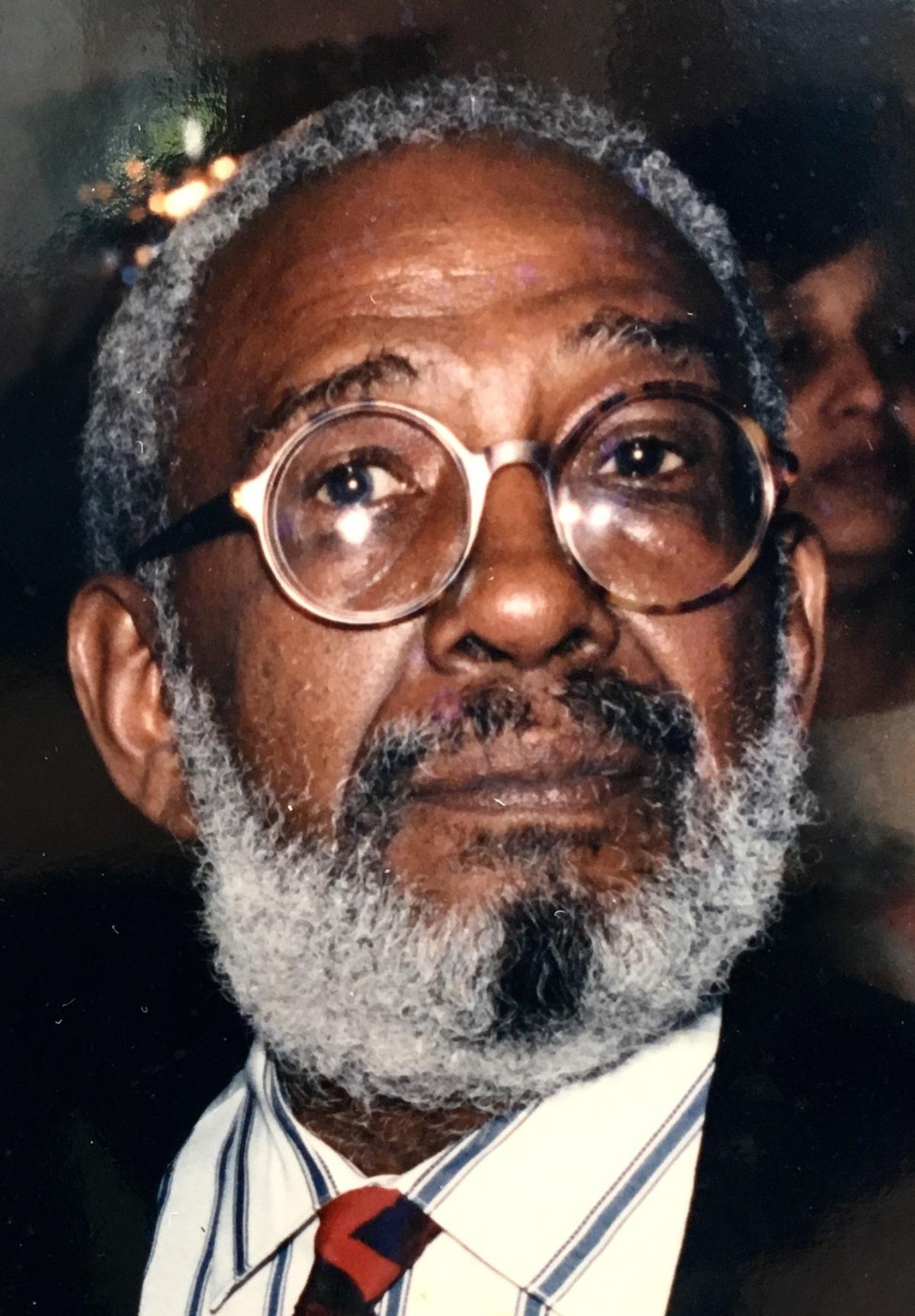

Photo by JOHN H. WILLIAMS -- Visiting at a reception at Southern University on March 12, 2009 are, from left, New Orleans attorney Lolis Edward Elie, Chancellor Freddie Pitcher Jr., Tennessee Circuit Court Judge D'Army Bailey, retired Judge Luke LaVergne, Stanley Halpin and attorney Walter Dumas. Bailey was one of the students expelled from Southern University in the early 1960s for participating in demonstrations against segregation.

- JOHN H. WILLIAMS

Prominent New Orleans civil rights lawyer Lolis Edward Elie died Tuesday at his home in Treme.

He was 87, according to his own accounts, which maintained that he was born in January 1930, though his birth certificate placed it in February 1928, said his son, writer Lolis Eric Elie.

Elie’s client list during the 1960s read like a who’s who of important civil rights figures in the state: Freedom Riders protesting segregation at bus stations across the South; the armed Deacons of Defense, who clashed with the Ku Klux Klan in Bogalusa; civil rights protesters in Plaquemine and other cities; members of the Congress of Racial Equality in New Orleans; and others.

His son heard from fellow writer Randy Fertel that his father had desegregated the Fertel family's restaurant, Ruth’s Chris Steak House, on North Broad Street. As the story went, Elie was eating at Ruth’s Chris with a judge who was trying to curry favor for an upcoming election. Another customer gestured at Elie and told restaurateur Ruth Fertel, “If you’re going to serve him, I’m leaving.” To which she replied, “Bye.”

Elie also represented Ernest “Dutch” Morial, who would become the city’s first African-American mayor, when Morial ran for a state legislative seat in 1967 and an opponent questioned his residency within the district.

Mayor Moon Landrieu, who hired an integrated staff after his election in 1970, a first for New Orleans, described Elie as one of his closest advisers and teachers.

During the 50 years that Elie practiced law, he was central to Louisiana’s civil rights movement, said retired Judge Calvin Johnson, who is now City Hall’s criminal justice commissioner. “If those of us whom he represented are like spokes on a wheel, Lolis was the fulcrum on that wheel,” Johnson said.

The two met when Johnson was 16, after an evening of protests that Elie would describe later as the scariest night of his life. Following a peaceful march in Plaquemine for civic reforms, police rode in on horseback to arrest and chase protesters, spraying them with tear gas and fire hoses and beating them with cattle prods and billy clubs.

Afterward, Johnson saw his lawyer walk into court and felt instant admiration for him. “The way he walked. The way he talked. The way this black man talked to this white judge. All of that. I fell in love with him. I wanted to be like Lolis,” Johnson said.

Elie grew up in New Orleans, became a merchant seaman after high school and ended up in New York City, where he worked odd jobs, saw shows at the Apollo Theater and heard some of the jazz greats of the time.

He was drafted into the Army and sent to California, where he was trained as a clerk. Afterward, he attended Howard University, then transferred home to Dillard University, where he helped to organize a sizable student chapter of the NAACP. It was suspended in 1956 after the Legislature required civil rights groups to publicly reveal their membership lists, putting members at risk.

In 1959, Elie received his law degree from Loyola University law school, got an office on Dryades Street and opened what become the legendary firm of Collins, Douglas & Elie with Loyola classmate Nils Douglas and Robert Collins, who had graduated from the LSU law school.

In April 1960, Elie became pro bono counsel for the Consumers’ League, whose leaders included the Rev. Avery Alexander and the Rev. A.L. Davis, as the group led a successful campaign on Dryades Street, where most shoppers were black. The boycott forced white merchants for the first time to hire black workers above the “mop and broom” level.

Later that year, Elie and his partners defended four student protesters: Rudy Lombard of Xavier University, Oretha Castle of Southern University at New Orleans, Cecil Carter Jr. of Dillard University and Lanny Goldfinch of Tulane University, all members of CORE.

The so-called “CORE Four” were arrested in September 1960 after a sit-in at the all-white lunch counter inside the McCrory’s store on Canal Street. Charged with criminal anarchy, the students faced possible 10-year prison sentences.

Elie and his partners successfully appealed the case, Lombard v. Louisiana, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where lawyer Jack Nelson argued the case. In 1963, the high court threw out the arrests.

In the mid-1960s, Elie testified at a hearing about out-of-state lawyer Richard Sobol’s prosecution for representing a defendant in a controversial Plaquemines Parish murder case despite the state’s ban on non-Louisiana attorneys in criminal cases.

Lawyer Anthony Amsterdam, now a New York University School of Law professor, recalled that, on cross-examination, the prosecutor asked, “Mr. Elie, is it not true that the condition of Negroes in the state of Louisiana has improved during the past five years?”

Elie answered, “Yes, but …” and continued on to give a two-hour answer that Amsterdam described as “easily the finest, most fiery civil rights speech I have ever heard.” Enrapt judges did not even call the usual break for lunchtime because Elie was in the middle of his answer, Amsterdam said.

Elie’s list of accomplishments, cases and clients “goes on and on and on,” Johnson said. “He is so much a part of the progress that we have made as a city, state and country, coming from the places we were.”

Besides his son, survivors include a daughter, Dr. Migel Elizabeth Elie; three grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

Visitation will be held from 4 to 7 p.m. on Friday at Rhodes Funeral Home, 3933 Washington Ave. It will resume and at 8:30 a.m. Saturday at St. Augustine Catholic Church, 1210 Gov. Nicholls St., until the funeral service begins at 10:30 a.m.

No comments:

Post a Comment